As the specialty-coffee industry matures, more and more research is being conducted to help us better understand the intricacies of the bean. On the farm level, those studies have included deeper looks into fermentation monitoring, varietals and the diseases that plague coffee trees. On the consuming side, research has been done on everything from the chemical changes that take place during roasting to the science of extraction in the brewing process.

However, one area that remains comparatively under-explored is coffee’s journey between those two stages. Transporting and warehousing both have significant potential impact on coffee quality, and Sustainable Harvest® has begun digging into the topic in recent years with a pair of studies. As we continue our research, we hope to jumpstart the conversation and fill in the knowledge gap about the effect of transportation and warehousing on coffee.

However, one area that remains comparatively under-explored is coffee’s journey between those two stages. Transporting and warehousing both have significant potential impact on coffee quality, and Sustainable Harvest® has begun digging into the topic in recent years with a pair of studies. As we continue our research, we hope to jumpstart the conversation and fill in the knowledge gap about the effect of transportation and warehousing on coffee.

Testing packaging effectiveness

We began our research into transporting and warehousing in 2012, and we decided to focus on Peru because our Lima-based office gives us easy access to exporters and producers there.

Because we had received some wet bags of coffee and jutey-tasting coffees from Peru the previous year, we decided to center the first experiment around different packaging options. We tried four approaches to packaging the coffee containers to avoid wet bags: hanging two types of bags (Protecpak and Nordic Dry) containing moisture-absorbing desiccants inside the container; packing the coffee beans in hermetic GrainPro bags; and putting a liner around the container’s perimeter.

Each packaging option was evaluated on its cost, how it protected against water, and the change in cupping results of pre-ship and landed samples. Of the four, Nordic Dry and the liner were the least expensive, each costing less than $100 per container. Protecpak was the next-most costly, and the priciest option was the GrainPro. As far as protection against water, while the two desiccant bags protect against moisture, they do not stop water from getting in. The GrainPro and liner, however, each protected the coffee from water. As for the variance in cupping results of pre-ship and landed samples, our experiment showed that the coffees transported in containers with liners showed the most consistency. All eight shipments showed less than a one-point difference between pre-shipped samples and landed samples.

Each packaging option was evaluated on its cost, how it protected against water, and the change in cupping results of pre-ship and landed samples. Of the four, Nordic Dry and the liner were the least expensive, each costing less than $100 per container. Protecpak was the next-most costly, and the priciest option was the GrainPro. As far as protection against water, while the two desiccant bags protect against moisture, they do not stop water from getting in. The GrainPro and liner, however, each protected the coffee from water. As for the variance in cupping results of pre-ship and landed samples, our experiment showed that the coffees transported in containers with liners showed the most consistency. All eight shipments showed less than a one-point difference between pre-shipped samples and landed samples.

The preliminary data gave us some indications of how to protect green coffee from water during the transporting process, but we were interested in digging deeper.

Measuring temperature and humidity

The next year, we aimed to investigate why wetness develops inside containers. Again we based the study on coffees from Peru, which we knew would provide us with interesting data in part because of the extreme temperature changes that occur during that journey. Peruvian coffees are shipped between August and December—the country’s warm season—and many of those coffees go to comparatively frigid North American cities like New York and Seattle.

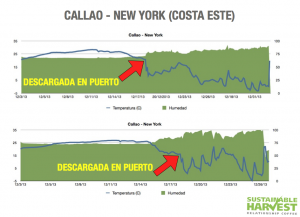

In order to study how those extreme temperature changes would affect the coffee, we outfitted 12 containers originating from Peru with meters measuring temperature and humidity. We recorded journeys from two ports—Callao in the south, and Paita farther north—to North American warehouses, measuring the temperature and humidity every 15 minutes.

Analyzing one of these journeys gives us a snapshot of what happens inside the container. On a voyage from Callao to New York, the temperature was around 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Farenheit) with 75 percent humidity when the container was loaded in Callao. When the container approached and then arrived in New York, the temperature steadily dropped—reaching as low as -4 degrees Celsius (25 degrees Fahrenheit)—while the humidity surged, reaching 100 percent at one point. What’s more, the temperatures saw extreme volatility once the container reached the port of New York, presumably once it was unloaded from the ship and individual containers became more susceptible to the elements.

Analyzing one of these journeys gives us a snapshot of what happens inside the container. On a voyage from Callao to New York, the temperature was around 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Farenheit) with 75 percent humidity when the container was loaded in Callao. When the container approached and then arrived in New York, the temperature steadily dropped—reaching as low as -4 degrees Celsius (25 degrees Fahrenheit)—while the humidity surged, reaching 100 percent at one point. What’s more, the temperatures saw extreme volatility once the container reached the port of New York, presumably once it was unloaded from the ship and individual containers became more susceptible to the elements.

For some of the shipments we measured, the meter was stuffed into a liner alongside the coffee—the same liner that protected the coffee from water in the earlier study. With those samples, we found that the coffee did not experience volatile temperature shifts, but rather a gradual drop as the coffee moved into North America.

Evaluation and action

In 75 percent of the cases we recorded, a rapid drop in temperature and a quick increase in humidity occurred as the coffee approached and then arrived at the North American port. We found a correlation between the falling temperature and humidity increase, as they both moved at similar rates, but in opposite directions.

That rapid temperature drop also indicates that there is condensation developing inside the container. Think of a cold bottle of Coca-Cola: When you remove it from the refrigerator and leave it outside, it will start sweating, or developing moisture on the outside of the bottle. An opposite situation happens in the container, where an inner warmth is put into a cold climate, and so the sweating effect happens inside the container.

That rapid temperature drop also indicates that there is condensation developing inside the container. Think of a cold bottle of Coca-Cola: When you remove it from the refrigerator and leave it outside, it will start sweating, or developing moisture on the outside of the bottle. An opposite situation happens in the container, where an inner warmth is put into a cold climate, and so the sweating effect happens inside the container.

From our data, we can assume that condensation is likely to occur during a coffee’s journey to port. With that fact in mind, what easy actions can be taken to protect coffee from that moisture? One simple tactic recommended to us from warehouse workers is to place corrugated cardboard on top and around the green coffee bags. This will both protect the coffee from water and absorb some of the moisture generated by condensation.

Ongoing research

Though we’ve now conducted two studies on this issue, we’re still in the early stages of discovering the effect of transportation and warehousing on coffee. We plan to conduct a third round of experiments on the shipment of Peruvian coffees in the upcoming harvest, and we hope to better connect the dots between what happens in the container and how it translates to cup quality. We look forward to further research and are excited to uncover new information on how the integral yet unheralded steps of transportation and warehousing factor into the final product.

.png)